The memories found in this city make Nazareth one of the holiest places in the world, and yet they are not the only memorable things that present themselves to the eye or the mind of the pilgrim in these places. There is practically no corner that does not remember something about Jesus, the one who lived here, his childhood and youth, his life in poverty, in joy and in the custody of the family, and here he learned, worked, prayed.

The origin of the word Nazareth (Natzrat or Natzeret in Hebrew; al-Nāṣira or al-Naseriyye in Arabic) dates back to the meaning of "to flower", as San Girolamo observed, but also means "to keep watch". The geographical location of this city in Lower Galilee confirms its role as an observation point. Nazareth is located along the most southern side of the hilly area that descends from Lebanon, at an elevated position above the opposed plain of Jezreel, the valley mentioned several times in the Bible and also known by its Greek name Esdrelon, that is about 350 metres above sea level.

However, for centuries Nazareth has resided in the hearts of pilgrims and travellers as "the flower of Galilee", holding the memory of the dialogue between the archangel Gabriel and Mary. By saying "yes" the young woman transformed the unknown village to the location of "here the Word became flesh", of the Son of God who became man, with the fruit of the Virgin’s breast that became flower, as proclaimed Bernardo di Chiaravalle in his comment about the mystery of Nazareth.

Mentioned for the first time in the Synoptic Gospels (the Gospel of Mark, which is the oldest, can be placed immediately before or after 70 A.D.), Nazareth is missing from the list of the cities of the Zebulon clan recorded in the book of Joshua (19,10-15). The small village is not even cited by Flavius Josephus who ruled the rebels of Galilee during the first revolt against Rome (66-74 A.D).

In 1962 a fragment of inscription in Jewish square capitals was recovered from the excavations of the Cesarea Maritima synagogue. The text lists the sacerdotal families which include that of Happizzez, resident of Nazaretin; the epigraph is therefore testimony to the existence of the village from the 2nd century A.D.

The Gospels hold two important pieces of information about the village: Nazareth had a big enough population to be able to boast the presence of a synagogue in which Jesus, one Saturday – the Jewish “Shabbat” – entered and unrolled the scroll of the prophet Isaiah, read and commented on the prophecy that concerned it (Luke 4,16-27). The other piece of information, of topographical character, is provided by the same passage of Luke, who remembers the cliff located in the village, where the furious crowd wanted to throw Jesus off after preaching in the synagogue (Luke 4, 28-30).

The first extra-evangelical but indirect mention of Nazareth is contained in a few Jewish sources from the end of the 1st Century A.D. with reference to the Jewish-Christian community who believed in "Jeshua‘ Hannozrî" (Jesus of Nazareth), the "nozrím" – nazarene – who together with the "miním" –heretics- were part of the twelfth oration of the prayer "Shemonè Esrè", a note inserted during the so-called "Council of Jamnia-Yavne."

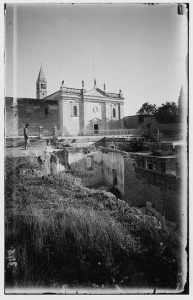

However, archaeology offers another type of testimony. The excavations identified the area where the ancient village stood and which Medieval and modern town planning incorporated into the current large Nazareth. The ancient village extended from north to south on the hilltop where the Basilica of the Annunciation, the Franciscan convent and the church of Saint Joseph now stand. The archaeological finds show that the first signs of life in the area date back to the Middle Bronze Age (2000-1550 B.C.).

The excavations conducted in the last century by the Franciscan Friars in the area of the sanctuaries, highlighted the remains of an agricultural village inhabited during the Iron Age (900-600 B.C.), that was gradually structured with simple dwellings constructed around caves used for their domestic work and for the recovery of animals. It was in this simple environment that Joseph and Mary went about their domestic lives and Jesus spent his childhood.

Nazareth was not far from Tzippori, the administrative and trading capital of Galilee, that Herod Antipater rebuilt between the 10th and 20th A.D. It should be noted that the inhabitants of Nazareth contributed to this reconstruction by lending their workforce.

It has been suggested that already in the first century, in Nazareth a group of Jews began to be distinguished who gave witness of their faith in Christ; Jesus’ relatives were part of these, of whom Hegessipus (2nd century), Julius Africanus (ca. 250) and Eusebius of Caesarea (4th century) spoke frequently. These texts bring Jude and his sons Zocer and James to memory. However, the Deacon Conon was also probably part of it: made a martyr in Asia Minor during the reign of Decius (249-251 A.D.) he in fact swore in court to being from Nazareth in Galilee and descending directly from the family of the Messiah.

In the third century, Eusebius of Caesarea in his "Onomasticon", that consist in a list of biblical place names, soon translated into Latin and completed by Saint Jerome, confirms that the "Nazareth" that gave the name “"nazarenes" to the first Christians was located in Galilee, 15 km from Legio, the ancient Megiddo and close to Mount Tabor.

During the Byzantine Era there is an increase of information about the Christian history of the village: Epiphanius (4th century) described the concern that Count Joseph showed in asking emperor Constantine for permission to build a few churches in Galilee and even in Nazareth itself. In his biography of Saint Helena, a later author from the 9th century confirmed that Constantine’s mother would have personally searched in Nazareth the house where Mary received the annunciation of the Angel and that would have held a magnificent temple.

Saint Jerome, who saw Nazareth with the disciples Paula and Eustochium, does not record the presence of a place of worship at Mary’s house, perhaps as it was managed by Christian Jews, in contrast with the non-Israelite church from which Jerome came.

In the 6th century, the two Jewish and Christian communities of Nazareth each had their own place of worship: the Jews had the Synagogue and the Christians had the church of Mary’s house, as the diary of any anonymous pilgrim from Piacenza records in (570 ca.). The source tells of a basilica where the pilgrim saw Mary’s robes, said to procure many good things to those who touched them.

With the arrival of the Persians in 614, the Christian community of Nazareth would have suffered a great deal of persecution from the Jewish community allied with Khosrau II. In 630, with the Byzantine conquest of Galilee, the Jews underwent an extreme persecution that formally brought an end to the presence of the Jewish community in Nazareth.

In 670 the pilgrim Arculf found two churches there, one of the Nutrition, the current church of Saint Joseph, and the other of the House of Mary, that of the Basilica of the Annunciation. The pilgrim made no reference to the synagogue belonging to the Jewish community.

There is little information about the Arab period that preceded the Crusades (638-1099).

In 723-726 Willibald noted the single church of the Annunciation, indicated again in 943 by the Arab historian and geographer al Mas'udi.

In 1099, once the Crusader kingdom of Jerusalem was established, Tancred of Hauteville was named Prince of Galilee and soon took on the renovation of the churches linked to the old evangelical memories, particularly Nazareth, Tiberiade and on Mount Tabor, as William of Tyre wrote, the historian at the time of the Crusades.

Saewulf, who visited Nazareth in 1102, told of a village in ruins, but also of a monastery located in the place of the Annunciation, which he indicated as extremely beautiful. In a few years Nazareth had become a bishop’s seat; in 1109-1100 that of Beit She’an was transferred there, and the Basilica of the Annunciation next to the aforementioned monastery was luxuriously restructured and equipped with lots of goods.

The chronicles of the Medieval pilgrims refer to the existence of many other holy places equipped with churches or chapels: Saint Jerome, Saint Zachariah also called Saint Mary of the Tremor, the Fountain of Mary not far from the church of Saint Gabriel, the Synagogue and Mount Precipice.

In the surroundings of Nazareth, the Crusaders build the church of Saints Joachim and Anna near Tzippori, to remember the apocryphal tradition that placed the house of Mary’s parents there.

Moreover, a fortress was built on the hilltop that rose above the ancient city with views over the plain of Zebulun beneath. Also on the Tabor, the mountain that dominated the entire Valley of Esdrelon, a fortress was built that held the Basilica of Transfiguration inside with the adjoining monastery.

The earthquake that hit Syria hard in 1170 would not have event spared Palestine, creating distruction and disorder and helping the Saracens in their fight against the Crusaders. The village of Nazareth was one of the places attacked by the Saracens. In order to support the Crusaders, Pope Alexander III asked the French faithful to give more donations for the church of Nazareth.

The first Crusader parable ended with the defeat at the Horns of Hattin on 4th July 1187, that provoked the taking of Nazareth by the Saladin troops and the killing of the Christians who had recovered inside the fortified Basilica. Raul of Coggeshall who visited the Holy Land during those dramatic years described the profanations that the "Sons of Sodom" perpetrated in numerous holy places. The peace treaty agreed with the Muslims in 1192 allowed the Christians to control the Basilica of the Annunciation. In this way, the flow of pilgrims was no longer restricted until the treaty was broken by Sultan Malik al-‘Adil in 1211.

The second Crusades began in 1229 with the ten-year agreement made between Frederick II and the Sultan Malik al Kamil who allowed the Christians the city of Nazareth as well as Jerusalem and Bethlehem. During this period, the pilgrimages began again and the Grotto of the Annunciation was also visited by King Louis IX of France who took part in the Holy Mass on 24th March 1251.

In 1260, the mamluks originating from Egypt launched a military operation against the Crusaders and against the last remnants of Ayubbid power in Syria and Palestine. In 1263, the Sultan Baibars ordered his militia to occupy and demolish the Christian places forever: the Basilica of the Annunciation and that of Tabor underwent the same sort of destruction.

During the mamluk period (1291-1517) that effectively begun after the fall of Acco, the last fortress of the Crusade, Nazareth became a depopulated and peripheral village: the adventurous pilgrims that reached it, proved the existence of a small chapel that protected the Grotto of the Annunciation, accessible on payment of a cup to the Muslims. The other Christian places noted by pilgrims at this time were the Source of Mary, next to the church of archangel Saint Gabriel, the church of the Synagogue, looked after by the Greeks and the grotto to Mount Precipice (Ricoldo of Monte Croce, 1294, Iacopo of Verona 1335, 1347, Fra Francesco Suriano, 1485). In the 14th century a small community of Franciscans was established in Nazareth but where soon obliged to leave it.

During the long Turkish Ottoman Empire (1517-1917), the Greek church benefitted from major support and advantages from the Sultans with respect to the Latin one, due to its geographical location in the same empire. In Nazareth, for example, the church of Saint Gabriel was occupied by the Greek clergy, as shown by the Custos Boniface from Ragusa during his pilgrimage to the holy places.

In 1620, by order of the Druse Emir Sidone Fakr-el Din II, the Custos Tommasso Obicini from Novara took possession of the Grotto of the Annunciation, the ruins of the basilica of Nazareth and those of the Transfiguration on Mount Tabor. So, the Franciscans revived the Latin religion there. The arrival of the Franciscans was followed by that of the Maronites and Melkites of the Eastern catholic church who still today form the majority of the city’s Christian community.

The Ottomon oppression against the Christians also affected the residents of Nazareth: in 1624 the village was looted by the order of the Emir Tarabei and the Franciscans fled together with the inhabitants to escape capture. On the death of the Emir Fakr-el Din (1635), supporter of the Franciscans, persecutions against the friars intensified. In1638 the inhabitants of the Christian village of Nazareth where attacked by the Muslims of Tzippori and, despite the attempt for defence made possible thanks to the powerful ruins of the Crusader church, the village was conquered, the dwellings burned and the inhabitants forced to flee. By the end of this century, the Franciscans were looking several times to make their rights heard against the continuous devastations ordered by the chief of Safed who set fire to the church and altars and repeatedly raided the convent in search of money.

Finally in 1730 it was possible to rebuild a small square church above the Grotto of the Annunciation, alongside the new Franciscan convent. It was blessed by the Father Custos Andrea of Montoro on 15th October of the same year. Since there was no governing authority, for a good part of the century the Franciscan community also performed civil and legal administration tasks both in Nazareth and the other surrounding villages on behalf of the Pasha of Sidon and of the governor of Acco. By the end of 1789, Nazareth returned to have an own Governor who resided in a palace and was honoured like a prince.

During the 1800s, the Ottoman empire began to experience the effects of Arab nationalist pressure that led to the more liberal and reformist policy of the sultan Abdülmecid I (1839-1861). Nazareth also benefitted from being more open and economically stable, allowing it to develop rapidly. The community was formed above all of Christians belonging to different rites (4,000 Christian followers and 2,000 Muslims).

With the increase of the number of faithful, the small Franciscan church was no longer big enough. Consequently, in 1877 the decision to lengthen its aisle was made. This church was used until the construction of the current one.

When in 1918 Nazareth was taken by British troops led by General Allenby, there was a population of around 8000, of which two thirds were Christian divided into Greek Orthodox, Melkites, Maronites and Latin. The English brought a fair amount of freedom and safety to the village and Nazareth experienced a new era that was prosperous like never before, becoming the administrative centre of Galilee. By the end of the period(1948) the number of inhabitants had more than doubled to around 18,000.

At the end of the mandate, there were 100,000 Christians in Palestine: around 10,000 of these were residing in Nazareth. 85% of the Palestinian Christians were in fact living in the north, divided in 24 groups of different names. 60% lived in urban centres such as Nazareth and Haifa and the rest were spread throughout the villages of Galilee. During the mandate, Nazareth saw different charitable, social and political activities flourish, supported by the various churches.

After the establishment of the state of Israel, in 1948, to which the first Arab-Israeli war was followed, the city became part of the new state. It was not simple for the local churches, made up of followers of Arab ethnicity in contrast with Jewish ones, the passage to the new Israeli state.

The wars for Israeli independence greatly changed the distribution of Arabs throughout the territory: at the end of the war, around 12,000 were evacuated from the Palestine Muslim villages, the presence of which provoked a sudden overturning of the percentages that continued over the years until the recording in the last decade of the twentieth century, of a presence of Muslims amounting to 70% of the entire population of Nazareth.

At the beginning of the 1960s in Nazareth there were just less than 60,000 inhabitants; after another fifty years the population had grown considerably, arriving at almost 307,000 in 2012. However, there is a fact that sets the town apart from the others in the North District, in that only 21.5% of the total population is of Jewish ethnicity.

In fact, for the rest of the district, the estimations of the Central Israeli Office for Statistics are very different: out of a population of 1,304,000 inhabitants, around 53% are Arabs, 44% are Jews and 3% from other ethnicities (2012 data). Therefore Nazareth confirms its persistent Arab physiognomy.

In 1957, a residential district emerged with a Jewish majority in the upper part of Nazareth known as Nazareth Illit ("Upper Nazareth") where the Palace of Justice and the Supreme Court of Justice and the Town Hall are located.

Moreover, in the last ten years the city has extended further onto the hills that surround it due to the construction of new residential areas where Arab families in particular reside.

Nevertheless, the town is still identified by the impressive new Basilica of the Annunciation that currently attracts millions of local and foreign pilgrims every year. The Basilica was inaugurated in 1969 on the architectural project of Giovanni Muzio.

Now the Latin parish church has around 5,000 followers and is one of the most dynamic communities of the Holy Land.

Brother Benedict Vlaminck was the first to survey the subsoil around the holy grotto. He published the results of his discoveries in 1900 in its "A Report of the Recent Excavations and Explorations conducted at the Sanctuary of Nazareth." In 1982 he discovered a second grotto with frescoes, then named after Conon, and located to the west of the venerated one and with Byzantine remains of mosaic floors. On this occasion it was the first find on the site of the Crusader church, which held Byzantine remains.

In 1889 and later between 1907 and 1909, the investigations were continued by Prosper Viaud and the results were quickly published in 1910, enhanced with beautiful illustrations in the volume “Nazareth et ses deux églises de l'Annonciation et de Saint-Joseph”. The discoveries had an immediate effect thanks to the unearthing of the mosaic with the crown and the monogram of Christ, together with the famous crusader capitals depicting the stories of the Apostles, found hidden inside a grotto beneath the floor of the convent’s parlour. It seems certain that the capitals, perhaps never used, were hidden at the end of the crusader period in order to protect them from being pillaged or destroyed by the Muslims.

Other excavations were carried out during the construction of the new Franciscan convent in 1930, but the diaries with the annotations were lost during the second world war.

The project for the construction of the new Basilica of the Annunciation, inaugurated in 1969, was the occasion to begin more thorough and extensive research on the history of the village and the ancient remains. The archaeological excavations were directed by father Bellarmino Bagatti, one of the founding fathers of the archaeological tradition of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, who had an expert understanding of the village’s antiquity.

In March 1955, the structures of the Franciscan Church, built in 1730 and extended in 1877, and the old convent and schools were knocked down. The space that was located to the north of the holy grotto, once finally free from structures was explored between April and June of the same year with the help of more than 120 local workers who digging on a daily basis closely watched by father Bagatti and his collaborator father Gaetano Pierri, cleaned up an area of around 90 x 60 metres. The investigations resulted above all in an understanding the village, its characteristic materials and development over time.

The work allowed for the exploration of the area to the east, south and north of the Grotto and shed light on the remains of the crusader and Byzantine churches and the ancient village.

As concerns the crusader Church, aside from the north wall and some other structures already well documented in the past, the apses and the exterior walls were completely unearthed, the cemetery that developed to the east was discovered and at the same time, many parts of granite columns and sculpted blocks that were part of the rich sanctuary’s decoration were uncovered.

The following sections of the Byzantine complex were investigated: the Church- with the apses, the three aisles and the vestry – the remains of the mosaic floors of the areas to the south of the church – and finally, the space reserved for the atrium where a water cistern was also unearthed.

The excavation of the village, of which the remains can still be visited today inside the archaeological area at the side of the Basilica, uncovering a system of natural and artificial grottos that were an integral part of the dwellings. Different storage bins for grain as well as cisterns for water were found. The latter contained ceramic, providing evidence that the site was used from the iron age up until modern day. A series of tombs dating back to the Middle Bronze Age were also discovered.

During the construction of the new sanctuary, it became necessary to better conserve the Byzantine mosaics. As a result, they were removed and positioned on a new base. Consequently, the opportunity to also investigate the areas beneath the mosaics arose. To the great surprise of father Bagatti and his collaborators, the remains of a more ancient pre-Byzantine building were brought to light, with clear and multiple signs of Christian veneration.

Overall, there were three main results:

P.Bagatti described his discoveries in the two volumes dedicated to “Gli scavi di Nazareth” (“The Nazareth excavations”) from the origins to the seventh century and from the twelfth century to today. These were dated and stamped respectively in 1967 and 1984 and followed by a publication translated into English.

In 1959, during the construction of the new Basilica, the Byzantine mosaics were removed in order to better preserved and relocated at the end of the work. On removing them, a surprising discovery was made: beneath the floor of the church and convent, various blocks of stone with painted and inscribed plaster belonging to an older religious building were found.

In particular, beneath the mosaic of the central aisle, right in the place where the small crosses and the monogram of Christ are depicted, a square-shaped basin cut in the rock with sides which are about two metres long and 1.6 metres deep and steps along the southern side was discovered. At the bottom of the basin, in the north eastern corner there is a circular well with a further hollow in the corner. In the wall plaster there are traces of the incisions made when the mortar was still fresh and interpreted by P. Testa as depictions of stairways (allusions to the "cosmic stairways"), crosses and boats.

The basin seems to have been closed and filled with various pieces of stone, ceramic dating back to the end of the 4th century and, in the upper layer, lots of fragments of white and coloured plaster bearing traces of graffiti written in the Syriac language. This basin is similar in shape to that of the crypt of Saint Joseph, but is not covered in mosaic. P. Bagatti, who initially thought it was designed for collecting wine, later decided that it was instead used for religious purposes. The similarity with that of Saint Joseph, led him to suppose that it was a baptism bath for Jewish-Christian initiation. Not all experts share this interpretation. More specifically, Taylor believes both the basins – of Saint Joseph and the Annunciation – more likely to be used for the village’s agricultural activities, for collecting pressed grapes for making wine.

Various building materials were found beneath the southern aisle and in the convent area. These were used to raise the level of the floor: pieces of painted and inscribed plaster, ceramics, illegible coins, fragments of roof tiles and pieces of marble slabs to cover the walls or floors. About seventy large architectural pieces were also discovered, including plaster, were also found that must have belonged to a demolished religious building: capitals, drums and bases of various columns made from local stone known as "nari", blocks which belonged to the arches of an aisle (double arch imposts), various worked cornices, door jambs and squared stones.

The excavations carried out since 1955 by P. Bellarmino Bagatti have brought to light part of the area occupied by the ancient village, today included in the modern Nazareth. In particular, it was investigated the space that was occupied, until 1930, by the Franciscan convent, built in turn over the bishop's palace of the Crusader era.

The town descended along the slope of the hill, in the space that today separates the two Franciscan sanctuaries of St. Joseph in the north and the Annunciation in the south. The village was surrounded to the north by a kind of natural amphitheater, formed by hills that reach the five hundred meters of altitude, while in the east and west it was bordered by valleys that descended towards the plain of Esdrelon. The steep side of the hill, on the east side, descended precipitously: today the eastern valley is still recognizable along Via Paolo VI, which connects the lower part of the city to the modern Nazareth Illit. The modern development of the city instead covered the western valley, which was to end in the area of the current souk, where there was also a source of water.

The northern, southern and western limits of the village have been identified thanks to the discovery of tombs dated from the Middle Bronze to the Byzantine period. The abundant presence of natural water sources, which facilitated the life of the village, is testified by the "source of Mary" located north of the evangelical village, which today flows from the rock enclosed in the Greek church of St. Gabriel and which is called from the local "Ain Sitti Maryam".

The excavations conducted by P. Bellarmino Bagatti, have highlighted the remains of an agricultural village frequented from the Iron Age II (900-600 BC), gradually structured around simple houses that exploited the underground caves, excavated in the tender limestone rock. They were part of the houses and were used for housework and as a shelter for animals. While the real houses, in masonry, were located on the surface or leaning against the caves.

Because of the different buildings built gradually in the area, there remained very few traces of the ancient houses and when P. Bagatti began the investigation he took the decision to immediately excavate up to the natural rock. The collection of archaeological data has therefore often been limited to traces found in the rock.

The agricultural character of the village is evidenced mainly by the numerous silos, pear-shaped holes with a circular entrance tapped by a stone, dug into the soft rocky limestone. The silos had to store the collected grains and even reached two meters deep. They were ingeniously arranged on top of each other, in several levels, and connected by tunnels that facilitated the storage of goods and the aeration of the grains. Along with the silos were found the cisterns that collected rainwater. Near for oil and grapes flanked by oil and wine cells, they were part of a production complex of which the stone millstones were also found.

By studying the connections between the silos and the arrangement of the water tanks it was possible to trace the hypothetical limits between the various properties: these had to be self-sufficient from the water point of view. Eugenio Alliata was able to intercept at least four distinct areas, with caves and silos connected, which were supposed to belong to four different dwellings.

The venerated cave, located on the southern side of the village, clearly belonged to one of these complexes that, at a certain point, also developed a productive area, equipped with an oil mill, of which a press with a squeezing collection tank remained. of wine or oil cells.

As already highlighted, the caves dug in the rock, like that of the Annunciation, were underground rooms of the houses. These consisted of one or more masonry rooms, perhaps also furnished with upper floors. The caves were used as warehouses in which to store the goods inside the silos, or as stalls for the animals; but they could also be used for various domestic activities and for hosting small ovens.

An excellent example of semi-rupestrian dwellings can be visited in the archaeological area next to the Basilica. We observe a cave with a small room in front of which the first row of stones remains. In this cave, by digging under the floor of the convent's parlor, Fr. Viaud discovered the five splendid Crusader capitals now kept in the museum. In the cave there is still an oven built in the north-west corner, and you can see some silos in the floor. Handles carved into the rock and a manger, refer to the use of the cave as a stable, at least for a certain period.

The history of the human occupation of Nazareth is summarized by some groups of ceramic types exhibited in the museum: they go from the 2nd millennium BC. at 1500 d.C.

The vases of the Middle Bronze I and II (200

According to the tradition of Epiphanius ("Panarion" XXX.II.10) it was the Count Joseph of Tiberias, a Jew converted at the time of Constantine, who asked to be able to build the first Christian church in the village of Nazareth, by the first half of the 4th century. There is no concrete evidence on the Count's success in his attempt to build the church, but the hypothesis is thought to be probable. Towards 383, the pilgrim Egeria saw a "grand and splendid grotto" where the Virgin Mary was said to have lived, with an altar inside and a garden where the Lord stayed after his return from Egypt.

In the testimonial accounts of the early centuries there is the tendency of people not to speak of places of worship that do not belong to their own tradition. An example are Saint Jerome and Epiphanius In the specific case of Nazareth, there is the theory that there had always been a place of prayer in the house of Mary, but this had not been found by the authors of noble stock, as it was conserved by the Jewish-Christian community. In fact Jerome, writing of his pilgrimage in the company of Paul and Eustoch, does not speak of churches in Nazareth, but only mentions the village. It is thus deduced that Nazareth was one of the places visited by pilgrims from the very early centuries.

A direct mention of the church was only to come in 570, with the visit of the Anonymous Pilgrim of Piacenza ("Itinerarium", V). He observed the village, but also the "House of Mary" converted into a church, as well as the synagogue officiated by the Jews.

Following the Arab conquest of 638 there came the description of the pilgrim Arculfus, who told the Abbot Adamnan of having seen two large churches in Nazareth: “one, where our Saviour was suckled”, the other “which is known to have been built over the house where Gabriel the Archangel spoke to Mary”.

Of these two churches only that of the Annunciation remained, as can be assumed from the testimony of Willibald in 724-26, which only speaks of the Annunciation, now at the mercy of the Muslims.

The last pre-crusade testimony is by the Arab historian al Mas’udi, in 943: he writes of having visited Nazareth and found “a church held in great veneration by Christians and where there are stone sarcophagus with bones of the dead, from which seeps a syrup-like ointment, used by the Christians to anoint themselves in prayer”. These were probably sepulchres placed in the church and highly venerated by believers.

Of the Byzantine church, the remains of which, surviving ruin, left space to the new ecclesiastical building built by the crusaders, consist in just a few walls on the foundation level, and sections of mosaic flooring. The digs of last century enabled an outline of the building layout: this consisted in a church oriented east to west, preceded by an atrium and flanked to the south by a monastery. Overall, these buildings covered an area of 48 metres in length from west to east, and 27 metres from north to south.

The Byzantine architects integrated natural environments into the church, made up of Grottos: this was not a new feature, in fact many Byzantine churches, such as those of Tabga or Getsemani, housed venerated rocks, or such as the church of Nativity, built around a series of grottos.

The church was made of three naves, the central one closed off by a semicircular apse. The grottos, at least two in number, were incorporated in the northern nave and were on a lower level: this is why the lateral grotto was accessed from the central nave by a stairway. There was a rectangular room at the end of the southern nave, interpreted as being a sacristy. The church exterior was 19.5 metres long and, including the atrium 39.6 metres long. The central nave was 8 metres wide.

The atrium leading to the church covered a large cistern still in use until 1960, and commonly known as the "cistern of the Virgin". Of the monastery there remains a row of rooms, while the area closest

to the church was irretrievably damaged by the crusade buildings.

The most well-known aspect of the Byzantine church is the mosaic flooring, present both on the area of the grottos and in the naves and monastery. Comparisons with a number of mosaics, oriented to the north, rather than the east, leads us to suppose that not all were made for the Byzantine church but were probably the flooring of an older building oriented towards the grottos.

The mosaic of the central nave, already noted during the digs of Father Prospero Viaud, is oriented to the north. It depicts the monogram of Christ on a white background, enclosed in a crown tied at the bottom with two tapes; in the lower section there are a number of crosses, including a great cross, with four small crosses alongside. It is worth noting that tiles of different sizes were used to complete this mosaic.

The mosaic on entrance to the grottos was unearthed by Brother Benedict Vlaminck, while conducting investigations outside the walls of the 18th century crypt. Along the west side of the Grotto of the Annunciation, he found the remains of another frescoed grotto, which had a mosaic on the entrance bearing the inscription in Greek, citing the deacon Conon of Jerusalem, as donor of the mosaic, under the same name of Conon of Nazareth, relative of Jesus and martyr of the 2nd century. This mosaic is also oriented to the north, like the mosaic of the central nave, and depicts a carpet with squares joined by diagonal lines interspersed with diamonds; crosses and other geometrical patters can be seen inside the squares. The inscription is found in a corner of the entrance to the grotto, known as the "Grotto of Conon". In this small grotto, there is a floor with a white background, featuring a larger square joined with diagonal lines to a smaller central square with diamonds alongside, the monogram of Christ is also found here.

The mosaics laid specifically for the Byzantine church are those oriented to the east, which can be seen in the southern lateral nave: there are also traces of the geometrical cornices that framed the entire nave. The oldest mosaic was later covered by a second. The primitive mosaic was with a fish scale frame containing a small flower, to then be replaced by a more elaborate cornice featuring a pattern of circles and diamonds. The elaborate details of this second mosaic distinguish it from all others found.

At the eastern end of the same nave, in the sacristy, there are traces of another mosaic, in the style of the that in the central nave and the grotto of Conon, with squares and diamonds on a white background.

The other areas of the monastery also had mosaic floors, conserved above all in two adjacent rooms, one small and one larger and rectangular. The first features a cornice of intertwined cords; the second shows a cross of flowering branches that form diamonds and an intertwined cornice surmounted by circles, limited to the eastern part of the room. In this larger room, towards the centre, the remains of a clay jug were also found, embedded in the floor.

The most precious feature of these mosaics is the presence of unmistakeably Christian symbols, such as the simple, great and monogram crosses. This element, typical of the Byzantine religious buildings, contributes to establishing the "terminus ad quem", i.e. the time frame within which the flooring was laid, as a decree by Theodosius II, in 427 (Cod.Just. i.8.I), forbade the representation of crosses in flooring.

The closest comparison for the mosaics of Nazareth is found in the church of Shavei Zion of the 5th century, which as well as featuring the cross conserve evident similarities in the geometrical patterns.

The Byzantine church also held a number of architectural fragments found in the digs: for example five pulvinos in white stone decorated at the sides with crosses, probably originally located between Corinthian style capitals and the start of the nave arch. Six high column bases were also unearthed, which probably belonged to the older building. Various other fragments belonged to the balustrade that divided the nave from the presbytery: the small square pillars supported the panels in marble decorated with grape vines, crosses, crowns and inscriptions in Greek, of which some fragments were conserved.

According to Father Bagatti, when considering both the stylistic and architectural features, the Byzantine church can be dated within a vast period, ranging from the 5th century to the 7th-8th century.

Various grottos were dug into the rocky hillside descending from north to south, and were used as part of the home or for production systems. Among these, only two were part of the Shrine: one larger version, venerated for the Annunciation, and a smaller and irregular one known as the Grotto of Conon. The grottos underwent several changes above all in the Middle Ages, when the grotto of the Annunciation was expanded and that of the Conon was partially demolished and set underground. However, it is quite plausible that from the very start their form would have been changed on insertion within the place of worship.

Today the grotto of the Annunciation features an irregular layout, running 5.5 metres from north to south and 6.14 metres from west to east, with a small apse in the eastern wall. Of the Byzantine era, there are remains on the northern side of layers of plaster, which in all likelihood covered the entire bare rock face of the Grotto. Another interesting feature, in the second layer, is a number of traces of graffiti.

The second grotto, known as the grotto of Conon, may once have been used as a memorial space with a raised bench. This area was set underground in the Middle Ages. On the eastern wall there are a remarkable six layers of overlaid plaster. The oldest plaster can now be seen, representing a strip with flowered plants and crown, and a painted inscription in Greek. According to Bagatti and Testa the painted inscription names Valeria “servant to our Lord Christ”, who made “a memory for the light”, in other words had the grotto decorated with the representation of a flowered Heaven in memory of a martyr, perhaps the same Conon of Nazareth. There are other examples of graffiti in the plaster, with a series of names and entreaties to Christ; a coin dates this oldest layer of plaster to the second half of the 4th century.

With the capture of Jerusalem by the Crusaders (1099), the Principality of Galilee was entrusted to Tancred of Hauteville, who established the capital in Tiberias. The Principality always remained a vassal of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, entrusted to families originating from the north of France, and specifically, from 1120, to the Bures dynasty from the Île-de-France.

A Latin bishop named Bernardo was already active in Nazareth in 1109-1110, head of a community of regular canons who carried out liturgical service and the welcoming of pilgrims. Under Bishop William (1125-1129), Bernardo’s successor, Nazareth became metropolitan archdiocese with jurisdiction over all Galilee and with two suffragan seats led by the abbot of Mount Tabor and the bishop of Tiberias.

The Grotto of the Annunciation was incorporated into a new solemn construction and was restored to being a destination site for numerous pilgrimages. The first testimony, written about the Crusader basilica, dates back to 1106-1107 and is by the Russian pilgrim Daniel, who tells of having seen a large and magnificent church erected in the centre of the village, which kept the grotto in which the angel declared the annunciation to Mary.

According to the testimony, the work for the construction of this impressive basilica began very early, probably thanks to the rich donations that Tancred made at the church of Nazareth. The basilica, served by regular canons , was next to the bishop palace and contained a guest area for welcoming pilgrims as well as a well-stocked library. Moreover, the archbishop had six knights and around one hundred and fifty sergeants at his command. The archdiocese became so rich that it could boast properties from the Levantine to southern Italy, a country that in 1172 had sixteen churches controlled by Nazareth.

The cathedral of Nazareth, in all its splendour, as proven by the archaeological remains, would most definitely have reflected the wealth and prestige of the archbishop. Besides the Annunciation, the Crusaders built at least two other churches, that of Saint Joseph and also of Saint Gabriel that included the well in which according to the Infancy Gospel of James, Mary met the Angel before receiving the annunciation in the dwelling.

Although there is no record of the amount of damage that the town suffered in the catastrophic earthquake that hit Syria and the city of Tyre hard on 29th June 1170, it is certain that Nazareth was subjected to the Muslim looting that followed the earthquake. The Nazarenes and religious people were captured and incarcerated. In December of the same year, spurred on by an appeal of Letard, Archbishop of Nazareth, Pope Alexander III wrote to the French Christians to ask for help for the town. Father Bagatti, who directed the excavations of Nazareth, believed that the church was also damaged in the earthquake. According to the archaeologist, the seism acts as a gap between the period of construction and that of decoration of the building, made possible by the contribution of France. The link between Nazareth and France must have been very close given that the architectural and sculptural style with which the cathedral was lavishly decorated is that of 12th century France, particularly of Bourgogne, Ile-de-France, the Viennois and Provence.

The Greek pilgrim Giovanni Focas of 1177 (or perhaps 1185) describes a grotto of the Annunciation that is different with respect to that of the first century and splendidly decorated. The indications let us believe that the construction and part of the decoration of the cathedral was already finished by the end of the century and before the Saracen invasions. In 1183, the inhabitants of Nazareth were besieged for the first time by the Saladin troops which were camped out on the surrounding hills, forcing the entire village to seek refuge within the strong walls of the church.

The church served as a fortress and protection even following the defeat of the "Horns of Hattin" in July 1187 when the inhabitants were besieged by the Emir of Saladin, Muzafar al-Din Kukburi. The siege led to the conquest of Nazareth, the killing of the inhabitants and the profanation of the holy building that, however, remained undamaged.

For around forty years, the city and its archdiocese remained in Muslim hands and only a series of truces and grants allowed the religious people to begin celebrating in the basilica again and welcome the pilgrims.

Nazareth and the road that connected to Acre officially returned under Christian control in January 1229 as a result of the agreement between Frederick II and the Sultan al-Malik al Kamil; the French control of the town was confirmed again in 1241, but it seems that the archbishop did not return there before 1250.

The last rich donation of sacerdotal furniture, paraments and vestments to the cathedral was given by Louis IX, King of France, who undertook a pilgrimage to Nazareth in March 1251.

Finally, in April 1263, the town was besieged by one of the Emirs of the Sultan Baibars: the village was plundered and the impressive Crusader basilica was destroyed forever. Spared from destruction, until 1730 the Grotto of the Annunciation remained the only place in the area still accessible to the pilgrims, who however had to pay a fee to the Muslim guards.

In eighteenth-century Nazareth, Christian communities lived in a time of greater tranquillity. Proof of this is the fact that in 1730 the Pasha granted the construction of a new church on the Sacred Grotto, to be implemented in six months, the time required for his pilgrimage to Mecca. On 15 October 1730, Custos Pietro da Luri consecrated the new church, which finally was able to accommodate the local Latin community now growing. On the opening day, in fact, more than a hundred Catholics received Confirmation.

The growth of the community would push the Custody, in 1877, to extend the length of the church, thanks to the support of Father Cipriano of Treviso, Commissioner of the Holy Land. The building lay in a north-south direction, with the Grotto of the Annunciation incorporated in the crypt under the chancel and preceded by a short hall. In the contemporary chronicles of the Holy Land, the church was described as the most beautiful owned by the Latin Church in the East. In 1742, Father Elzear Horn made a number of drawings clearly showing the layout of the Grotto under the chancel, reachable by a staircase. In the anteroom to the Grotto, there was the Chapel of the Angel, with groined vault ceilings supported by the four granite columns still visible today. In the vestibule, on the left, there was an altar dedicated to San Gabriele. A wooden altar was located in back of the cave, richly decorated with a painting of the Annunciation and, under the altar, the exact point of the Incarnation, shown by the following silver writing, “Verbo Caro hic factum est.” All eighteenth-century depictions show the two broken and unbroken columns, which for centuries have indicated the place where the Angel Gabriel and the Virgin stood during the Annunciation. The place was connected by an ancient tunnel to the cave called "Cucina di Maria" and the Franciscan monastery.

The upper church had an altar on either side, one dedicated to San Francesco and the other to Sant’Antonio da Padua, and two side altars in the apse, dedicated to San Giuseppe, husband of Mary and to Sant’Anna, mother of the Virgin.

Already at the end of the First World War the Custodia proposed, to Pope Pius IX, the idea of building a more worthy shrine, in the place of the Annunciation. Many years later, in 1954 the propitious opportunity arose: the first centenary of the proclamation of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception. To celebrate this anniversary, padre Custode Giacinto Faccio decided to start the work, which involved demolishing all the 18th century structures and conducting archaeological investigations of the ancient ruins.

The renowned architect Antonio Barluzzi, who had designed major shrines for the Custodia, such as the Getsemani, Tabor and Dominus Flevit, was the first to be assigned for the design of the new shrine. An article with drawings of his designs was published in the magazine of Holy Land in 1954. The design envisaged a great church with central layout, covered by a cupola and flanked by four bell towers; it was designed, as was the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, with the worshipped grotto at the centre.

The rediscovery of the ancient village and the archaeological remains of the various buildings of worship that followed over the centuries, revealed an age-old and uninterrupted Marian veneration, and thus became an indispensable element to be considered in the design of the new shrine. Along these lines was also the Holy See, from which came the invitation to best conserve the remains of the ancient village and various churches. This recommendation led the Custodia to promote a new project, this time assigned to the Italian architect Giovanni Muzio, on proposal by Custodian Father Alfredo Polidori, who valued the experience of Muzio in the design of religious buildings, in particular for the Friars Minor, for whom he had designed the church of Santa Maria Mediatrice in Rome, with the annexed Curia Generalizia.

The needs to be met were manifold: to build a new Marian shrine that could welcome millions of pilgrims from all over the world; to conserve as far as possible the crusade, Byzantine and pre-Byzantine remains in view, as testimony to the long-standing worship of the location; to overcome difficult topographical conditions due to the steep slopes of the hills; to create a practical location, easily managed even by a limited number of religious figures and which could also be host to the parish community activities of Nazareth.

The architect became so impassioned with the project that he wavered his fee.

He designed a church founded on the crusade walls and divided onto two levels, so that on the lower level followers could stay and pray in front of the grotto of the Incarnation of the Word, in a simple but capacious area, while a large upper church would be used to celebrate the glorification of Mary over the centuries and the continents. For this reason, he chose to decorate the walls depicting the various Marian events that have occurred across the various regions of the world. Muzio also thought of a large central oeil-de-boeuf window open above the Grotto, so that the two churches could merge into one, crowned by a polygonal cupola in the shape of an inverted crown of flowers terminating in a skylight, with the function of indicating, like a star, the Holy Place from afar.

With the approval of the Holy See, the works started and proceeded uninterrupted. The Custodia met the onerous costs of the work also thanks to the generous response of many donors who, through the pages of the magazine “The Holy Land” and the precious help of the Commissaries of the Holy Land, were kept up-to-date with the phases of construction.

Works to prepare the site started in 1959 and the agreement with the contracted firm was signed in September of 1960. In 1964, Pope Paul VI, during his pilgrimage to the Holy Land, visited the new Shrine under construction.

On Sunday 23 March 1969, after eight years of work, the shrine was finally consecrated in the presence of Cardinal Gabriele Maria Garrone - at the time Prefect of the sacred Congregation for Catholic Education -, of the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem S.B. Monsignor Gori, of the Minister General of the Order of Franciscan Friars Father Costantino Koser, of the Custos of the Holy Land Very Reverend P. Alfonso Calabrese. The custos who alternated during the planning and production of the work were P. Giacinto Faccio, P. Angelo Lazzeri, P. Alfredo Polidori, P. Lino Cappiello and P. Alfonso Calabrese.

Boniface of Ragusa, who was twice Custos of the Holy Land, wrote in 1567 that about twenty years earlier the friars were in Nazareth, where they guarded the Church of the Annunciation. At one point, due to unrest in the country, they had to take refuge in Jerusalem leaving the keys to a local Christian who, "until now guards the house, opens and closes the church and holds two lamps lit with oil, which the father Custos gives him."

With a firman – a Sultan’s decree – obtained from the father superior of the Holy Land on 15th June 1546 the Franciscans were granted permission to restore their church in Nazareth. Evidently, it was the church of the Annunciation built by the Crusaders and destroyed, among whose ruins the worship in the Grotto continued. The church, however, was not restored because of the continuous attacks against Christians that caused the friars to leave.

The Franciscan presence in Nazareth was made official starting in 1620. In that year, the Custos Thomas Obicini da Novara obtained donation of the venerated Grotto by Druze Emir of Sidon, Fakhr ad-Din II. With the cave now in the hands of the Franciscans, father Jacques de Vendôme, a brave and energetic friar of French nationality, remained to guard the Grotto along with two other brothers who joined him from Jerusalem. He built some temporary cells on top of the Crusader ruins and a small room adjacent to the Grotto, used to celebrate functions.

Starting with the killing of the emir in 1635, the friars lost their protection and the Christians of Nazareth were targeted by the Turks in the two following centuries: the Grotto was repeatedly sacked, stripped of furniture and damaged while the friars were beaten, jailed and even killed.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, both the abandonment of the convent of Nazareth and the forced retreat to the Franciscan hospice of Acco or to Jerusalem were repeatedly required. In the 17th century in particular, extortion and looting by the governor of Safed brought the friars to seek justice repeatedly in front of the Imperial court in Istanbul, both to have their goods back and also to have the extortion of money cease along with the restoration of the rule of law in the country. Despite this, their tenacity brought them to open the first parish school in 1645 and to give hospitality to pilgrims in the hospice they set up between the simple cells of their small convent. Even pilgrimages - processions related to religious holidays - despite being hampered, departed from Nazareth to the nearby places of the gospel memories such as Cana and Tiberias.

In 1697, given the continuing difficulties, the Franciscans thought of a solution to better cope with the continuous instability. For this reason they "rented" the village of Nazareth and, over time, three other villages not very far from it (Yaffia, Mugeidel and Kneifes). To keep the rent, the friars had to pay a hefty fee. This practice kept constant until 1770, when they gave up because of the unsustainable taxation. In practice, the father Custos of Nazareth took on the task of judicial and civil servant, collecting fees for the Pasha of Saida and the governor of Acco. It was an office comparable to that of Emir, in other words, Lord of the place.

During the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire began to suffer from internal nationalist movements that were agitating the Arab world. Out of that came a more liberal and reformist Sultan Abdülmecid I, who granted greater openness also towards the right of religious expression. For example, in 1867 the friars were able to open a novitiate for the training of young Franciscans in Nazareth, which was closed in 1940. It was a century of growth for everyone: the Latins, which in 1848 counted 600 faithful, had become double that by the end of the century. Social and parish-linked activities grew as well: the opening of the first school for girls dates back to 1842, joining the two others that the Custody was inaugurating in Jerusalem and Bethlehem. A hospice for pilgrims was built in 1837, which was destroyed by an earthquake and a flood. The current Casa Nova, built in front of the basilica, dates back to 1896. In addition to hosting famous guests such as Napoleon Bonaparte, the Casa Nova also welcomed many Palestinian refugees from the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.

Today the Franciscans in Nazareth have a parish community of 5,000 faithful gathered around the Sanctuary of the Annunciation. The Franciscan Terra Sancta College occupies a large building connected to the convent and has about 800 Christian and Muslim students, thus fostering religious integration. Other social activities are turned to the elderly in the nursing home and the disabled who benefit from having their own centre. Additionally, the Custody built some homes to support the persons in need.

Looking down over the city of Nazareth, the truncated conical dome stands out and towers above the other buildings, located on the top of the elegant octagonal base of the Basilica of the Annunciation. The huge, square structure, similar to that of a fortress, is set alongside the Franciscan convent.

The construction was designed by the Italian architect Giovanni Muzio and built by the firm Solel Boneh from Tel Aviv thanks to the work of the skilled brick layers and stone cutters of Nazareth.

The work was completed on 23rd March 1969 and inaugurated on the day of the Feast of the Annunciation of the same year.

The basilica is 55 metres high and covers 65 x 27 metres. Its dimensions have earned it the title of being the biggest monument of its kind in the Middle East.

On entering the main gate, you find yourself facing the large façade and the entrance to the lower basilica.

A statue of the Virgin and a fountain which flows down onto the wall has been located on the left for a few years.

A beatiful portico extends along the whole southern perimeter of the sanctuary and delineates the large square.

Beneath the portico you can admire the depictions of the Virgin by various artists, representing sanctuaries of Mary throughout the world. This theme is continued inside the upper basilica. The bell tower stands at the back, in the south eastern corner of the basilica.

Located inside a large enclosed space, the basilica has a modern façade decorated with bas-relief and inscriptions which summarise the story of the Mystery of the Incarnation, works by the Italian sculptor Angelo Biancini.

The white stone façade is slightly concave and separated by horizontal stretches of pink stone decorated with the four elements of the world that, according to ancient cosmography, Christ would have had to cross to be incarnated: fire, air, water and earth. Three window series, made up of smaller windows arranged in a pyramid, give a vertical slant to the solid façade.

Looking up, there are two bas-relief depictions with Mary and angel Gabriel on the moment of the Annunciation, with the Latin phrase "Angelus Domini nuntiavit Mariæ" at its base.

In the section below the four evangelists are symbolically represented: Matthew as a winged man, Mark as a lion, Luke as an ox and John with the image of an eagle. At the sides, a few inscriptions in Latin refer to the prophecies of Christ and Mary in the Old Testament: on the left, the passage of Genesis «Ait Dominus ad serpentem. Ipsa conteret caput tuum et tu insidiaberis calcaneo eius» (Gen 3,14-15) and on the right that of Isaiah «Ecce Virgo concipiet et pariet filium et vocabitur nomen eius Emmanuel» (Is 7, 14b).

The hymn of John «Verbum Caro factum est et habitavit in nobis» (Gv 1,14) appears above the three entry doors.

The façade is flanked by two octagonal towers. On the top of the tympanum the three-metre high bronze statue of "Christ Blessing" can be seen: the whole façade, including the famous Son of God «made of a woman, made under the law, to redeem those under the law, that we might receive the adoption of sons» (Gal 4,4-5).

On the architrave of the central door there is an engraving of the monogram of Christ, the ancient Christian symbol that can also be found in Byzantine mosaics inside the lower church. The embossed bronze and copper shutters of the doors, created by the German sculptor Roland Friedrichsen, represent the life of Christ from his birth to his death on the cross.

The central door is larger and framed by a red granite doorway. The creation of the Holy Door, a gift from Bavaria, is the work of the sculptor Friederichsen.

The Holy Trinity is engraved at the centre of the architrave, that lights up the world as God the creator, God the savior, God the Father. The symbols that distinguish it are: the eye of providence or the Father eye, the cross of Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit as a dove.

The doorway features high relief bronze biblical depictions. The shutters represent the stories of the life of Jesus in sixteen episodes, of which six are illustrated in high relief: the left shows his childhood, the flight into Egypt and the life in Nazareth while the right illustrates his public activities including the baptism, the Sermon on the Mount and the crucifixion.

Biblical figures from the old and new testament can be seen on the door jambs: on the left, Adam, Solomon, Isaac, Jacob, Noah, Abraham, Elijah, Jeremiah, Samuel, Moses and David; on the right, Peter, Thaddeus, Matthias, Thomas, Simon, James, John, Bartholomew, Phillip, Andrew, Matthew, James son of Alphaeus. Jesus represents the union between the old and new.

The embossed copper side doors are decorated with biblical scenes from the Old Testament along with the figure of Christ as the Messiah.

Three scenes that recall the story of the salvation of Adam and Eve are represented on the left door, from the story of Noah and the great flood through to the sacrifice of Isaac by his father Abraham. On this door, referred to as "Adam’s", the facts that preceded the coming of Christ are displayed: God attempted to create an alliance with man in spite of the original sin.

The captions that surround the scenes are taken from the texts of the Old Testament.

The right door, in continuity with the left door, shows the excursus on the biblical figures, that cover the story of the salvation. Among the relief figures you can make out King David and Jonah, characters that directly relate to Jesus.

The southern side of the basilica is enriched with the original and elegant façade of the "Salve Regina", from which you access the lower part. Mary is here glorified as the mother of hope and mercy. The prayer is engraved on the stones of the pinkish walls, starting with the first upper line. At the centre you can make out a picturesque balcony opening onto the upper basilica. Immediately below, the life size bronze statue of the Holy Virgin, by the Italian Franco Verroca, shows Mary as a young girl, as she would have been at the moment of the Annunciation.

Before the bronze door there is a small pronaos decorated with mosaic and marble, a work by the US F. Shardy. This is divided into lots of tiles and narrates the life of Our Lady; it is a gift from the United States of America. The figure of the Virgin Mary is glorified on the shutters via the scenes of her life from childhood to the Assumption, and the image of Mary as "Mater Ecclesiæ", who protects the universal church with her coat, represented by a large group of holy buildings.

At the sides of the atrium there are two mosaics: one represents the image of the "Navis Salutis" of Peter while the other features the harp of King David. Both the images recall the elements of ancient tradition, particularly the Boat that represents the Church crossing the waters without ever sinking.

The entrance to the lower basilica is very impressive and invites to prayer. The space has been deliberately designed to highlight the Grotto and the archaeological remains that tradition attributes to the place of the Annunciation and the Incarnation of the Savior. The centrality of the cave allows the visitor to embrace the whole environment with a single glance.

The structure of reinforced concrete rises on the plan of the ancient Crusader basilica, whose perimeter was brought to light in the excavations of the first half of the twentieth century. The three apses are reconstructed on the original of the XII century. At the center of the main apse is a bronze cross; in the north one there are the parents of Maria, the saints Joachim and Anna, and in the southern one there is an 18th century picture of the Annunciation, preserved inside the Grotta Santa from 1754 to 1954, the year of the demolition of the eighteenth-century church.

The Grotto of the Annunciation is surrounded by a wrought iron gate and is surmounted by a suspended canopy, decorated with gilded copper reliefs, which depict the scene of the Annunciation.

The venerated Grotto is at a lower level than the current basilica.

In the Sanctuary built by the Franciscans in the eighteenth century, it was located under the presbytery and was accessed by a front-facing staircase. After the archaeological excavations of the last century, it was decided to leave in view the S. Grotta and the ancient remains, to give even more importance to the place revered since the first centuries of Christianity.

Fragments of walls and mosaics of the original prayer hall and of the subsequent Byzantine church are visible. A basin, found under the Byzantine mosaics, probably belongs to the original housing complex which also included the Grotta, perhaps later used for baptismal rituals.

In front of the S. Grotta, within the perimeter of the Byzantine church, the space for liturgical celebrations has been set up.

The penumbra allows the visitor to enjoy the contrast with the light that reveals the place of the Announcement, illuminated by the white stone of the Grotto.

The silent, cosy atmosphere, enhanced by the harmonious architecture is evident as soon as you enter the church and fits with the Sanctuary that it encloses. The northern wall – on the left as you enter – is made of a modern wall build onto the Crusader church’s strong wall, from well-made stones separated by half-columns. The windows which are a work by Lydia Roppolt and a gift from Austria, reflect an old style. The remains of the Byzantine basilica containing the new celebration altar in front of the Grotto can be seen in the centre, enclosed by an iron balustrade.

Beneath the Byzantine age mosaic floor there are plastered stones that belonged to the older place of worship. Marks left by pilgrims over the centuries can be spotted in the plaster which is now displayed in the archaeological museum of the Basilica. A basin with steps was found beneath the mosaic, almost exactly the same as that found in the church of Saint Joseph.

At the bottom of the lower basilica there are the three apses, partly restored and partly rebuilt to reflect the Crusader style. The two on the sides, with altars facing towards the people, have been rebuilt with ancient stone; the central one is decorated with an embossed copper cross by the sculptor Ben Shalom from Haifa, a copy of the one that spoke to Saint Francis in the church of San Damiano. The organ pipes are located in the apse and are made by the famous Tamburini firm of Cremona.

As in the other sanctuaries appearing in the Christian memorials of the Holy Land, the Grotto of Nazareth also bears reference to the "HIC" exact location in which the gospel events occurred: here the Virgin Mary heard the words of the Annunciation; here she pronounced the fiat; here the Word became flesh; here purity and virginity fused with maternity while remaining intact.

The Grotto of the Annunciation opens like a small sanctuary, the place of the Annunciation of angel Gabriel and Mary. To reach the level of the Holy Grotto and of the small grotto beside it, you descend the seven steps of the eastern stairway and walk along the chapel of the Angel towards the stairs for ascending again; these two staircases correspond to the entrances built in the Crusader era. They would have been similar to the ones that still today lead inside the grotto of Bethlehem.

The venerated Grotto underwent many changes over the various eras in order to ensure the site could be visited and religion could be practiced there. Today its appearance is a small rocky chapel, made partly of natural rock and partly of stonework.

You can already see from the outside two elements of crucial importance which testify that the place was part of the ancient village. These are two large grain containers dating back to the time of Jesus and the immediately subsequent period. These containers with circular holes of which a few traces remain, are located on the right and left of the Grotto’s entrance door, beyond the wrought iron balustrade. Moreover, above the Grotto and along the sides, the Crusader pillars that supported the arches of the large church can be seen.

On entering the Grotto, you can make out the remains of the natural rock that formed the room, as well as sections of stonework partly rebuilt in shiny white stone. The ceiling, that underwent a few changes in the past to make the Grotto seem like a chapel, is slightly rounded. In the Crusader era, the Grotto was blocked off and recarved on the outside to allow a new holy building to be inserted; part of the vault, probably collapsed, was also replaced with Crusader stonework. Recently, holes have been made to ensure a good ventilation of the room since it undergoes significant deterioration due to the high level of humidity inside.

Three columns were inserted to support the pillar that the Crusaders built above the Grotto: two can be seen on the left, outside the Grotto’s new wall and one on the inside, broken and suspended. The largest column of the two outer ones was referred to by the pilgrims as "the Angel column"; the broken one inside was called "the Virgin’s column", because it was believed to indicate exactly the place where Mary was sitting during the Annunciation. The column that sticks up from the roof of the Grotto was split open in the Ottoman period, because it was thought to contain a treasure.

The main altar bears the inscription «Verbum caro hic factum est», "HERE" the word became flesh, part of the Franciscan sanctuary of 1730.

Entering on the right, there is a small apse created for one of the five altars that were in the Grotto and in the Chapel of the Angel until halfway through the last century. The apse was plastered several times and the pilgrims made various inscriptions there that have unfortunately been lost due to the strong deterioration of the walls.

The room to the north, further inside the Grotto, is a semicircular shape and has preserved an altar dedicated to Saint Joseph over the centuries. It now contains a column holding the tabernacle.

Behind the altar of the Annunciation, a grotto better known as "Mary’s kitchen" can be reached via a stairway built into the wall.

On entering the bright upper Basilica, it is immediately evident that there is more space than in the lower Basilica. All the iconography is dedicated to the celebration of Christ, Mary and the Franciscan order.

The lower area can be reached via two spiral stairways located at the sides of the entrance. The main entrance is located to the north of the building, in front of the large roof terrace that protects the archaeological remains of the ancient village and connects the square of the Basilica to the convent and parish space.

There are two doors located to the north: one on the left, known as the Mater Christi or the "Ecclesia ex Circumcisione", the other, to the right, known as the "Mater Ecclesiae" or the "Ecclesia ex Gentibus".

The tympanum on the left door portrays the nativity scene in glazed ceramic while the one on the right door shows Mary with her cloak open, welcoming the faithful. Both high reliefs are a work by Angelo Biancini.

The bronze shutters, a work by the Dutch sculptor Niel Steenbergen, depict the two strains of the church: Jewish and non-Israelite. On the left door, that represents the church of Jewish origin, there is a representation of the tree of Jesse, the Annunciation, the Adoration of the Shepherds and the Call of Peter. In the second, the one on the right, there are biblical images that recall the non-Israelite strain of the church: the experience of the prophet Jonah, the visit of the Three Kings, Pentecost and the conversion of Saul.

The octagonal baptistery is located outside in front of the door. The floor of the square is decorated with the representation of the Canticle of the Sun of Saint Francis of Assisi and, with other symbols that recall the Franciscan spirituality.

The space inside the basilica is bathed in bright light and the vibrant colours of the various Marian images that decorate the church. The light enters from the dome and the wide windows inspired by Mary.

The central apse is decorated by the majestic mosaic with the representation of the statement of the Creed that declares the Church to be "One Holy, Catholic and Apostolic".

The theme of the Virgin, Mother of God, is present in lots of the decorations: even in the bronze candelabra located in the presbytery where the history of salvation from the origins to the Roman church is depicted. The side apses contain the chapels dedicated to the "Most Blessed Sacrament" and the "Custody of the Holy Land" with the Franciscan saints.

The walls of the Church depict a celebration of Mary: images of the Virgin coming from various sanctuaries of the world follow to mark out the Incarnation of Christ, as presented in all the cultures of the world. The panels come from various countries of the world. On the right wall: Cameroun, Hungary, Brazil, the United States, Poland, Spain, Italy. On the left wall: England, Australia, Argentina, Venezuela, Lebanon, Japan, Canada.

The windows of the south and west façades represent various elements of the Annunciation and are realised by the Parisian artist Max Ingrand: the shape of the pointed arch reflects the style than can be found in old Gothic cathedrals.

On the marble floor, a work by the artist Adriano Alessandrini, the Marian dogma defined and privileges granted over the centuries by the Council Fathers and the Popes, starting with the Council of Ephesus in 431 AD, in which the divine maternity of Mary was established, are depicted.

Finally, we can turn our attention to the starlit oculus that opens onto the remains of the Grotto of the Annunciation.

The apse mosaic, created by the artist Salvatore Fiume is based on the theme of the "One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic" church, in the light of the "Lumen Gentium": the cosmic church, i.e. that of yesterday, today and forever; the hierarchical and charismatic church together, the sacrament, in Christ, of the close bond between humanity and God.

This theme is written in golden letters along the side of the crown at the top of the mosaic: "Credo unam, sanctam, catholicam et apostolicam Ecclesiam."

Christ is at the centre extending his arms towards the whole of humanity who is walking towards him. Peter is at his side with the keys of the kingdom of God along with the Mary Immaculate Queen in the background. At the top, the eye of God and the Holy Spirit as a dove complete the trinity depiction. On the bottom right, the popes who governed the church from 1914 to 1968 are represented: Benedict XV, Pius XI, Pius XII, John XXIII and Paul VI.

On the left of the main altar there is a chapel dedicated to the Custody of the Holy Land: the coat of arms with a red cosmic cross is shown in the centre. The mosaic that decorates the chapel, a work by the artist Glauco Baruzzi, is entirely dedicated to the celebration of the Order of Friars Minor, with the image of stigmatic Saint Francis and the first Franciscan martyrs. King Robert of Anjou and Sancia of Aragon, figures who significantly contributed to the presence of Franciscans on the Holy Land feature on the jambs of the chapel.

The chapel of the Most Holy Sacrament is on the right, a work by the Spanish artist Rafael Ubeda, who with a very original style inspired by Picasso studied the elements of traditional Christian symbology, representing them on the jambs of the chapel: fish, bread, the anchor. The chapel is dedicated to all the saints of the Church.

In the chapel vault, the artist develops the theme of universal reconciliation after the struggle between good and evil experienced by humanity: the birth of Jesus represents the victory of light over the darkness of evil.

The dome stands on the top of the 40-metre high basilica and is entirely constructed of prebuilt panels decorated with a continuous series of zigzags that can also be interpreted as endless repetitions of the letter "M" for Mary. The arrangement of the panels in rays imitates the petals of a lily.

The light floods from the central opening of the roof lantern and illuminates the whole dome. Sixteen triangular windows form an intensely bright circle that makes the dome ethereal.

The exterior is covered in stone up to the level of the loggia with arched openings. The loggia and the roof lantern are also made of stone while the perimeter is covered in copper.

The windows of the dome are made of concrete and coloured glass by the Swiss painter Yoki Aebischer and represent: the Apostles, the Saints Joachim and Anna, Saint Ephrem the Syrian, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux.

The suspended platform, on entrance to the upper basilica, was built for two purposes: to protect and enable views of the archaeological digs of the ancient village of Nazareth and to join the shrines of the Annunciation and Saint Joseph, via the route that runs alongside the Franciscan monastery..

At the centre of the platform there is the baptistery created by the couple Bernd Hartmann-Lintel and Ima Rochelle, German artists in bronze and mosaics, featuring the interior that represents the Baptism of Jesus in Jordan with the descent of the Holy Spirit. The baptistery conserves the remarkable wooden reconstruction of the crusade basilica, according to the hypothesis of P. Viaud, who studied the building at the start of the 1900s.

The floor of the platform is decorated in black and white stone with the coat of arms of the Order of Franciscans and the Custodia and with a large vine overflowing with grapes and birds feeding from them. An image that recalls an ancient Paleo-Christian iconographic motif, which alludes to Jesus, real life, that nourishes the believers. The tree may also remind the observer of that of the parable of the small grain of mustard that becomes a large plant: "The Kingdom of Heaven is similar to a grain of mustard, which a man took and planted in his field. It is indeed smaller than all seeds. But when it is grown, it is greater than the herbs, and becomes a tree, so that the birds of the air come and lodge in its branches (Mt 13,31-32).